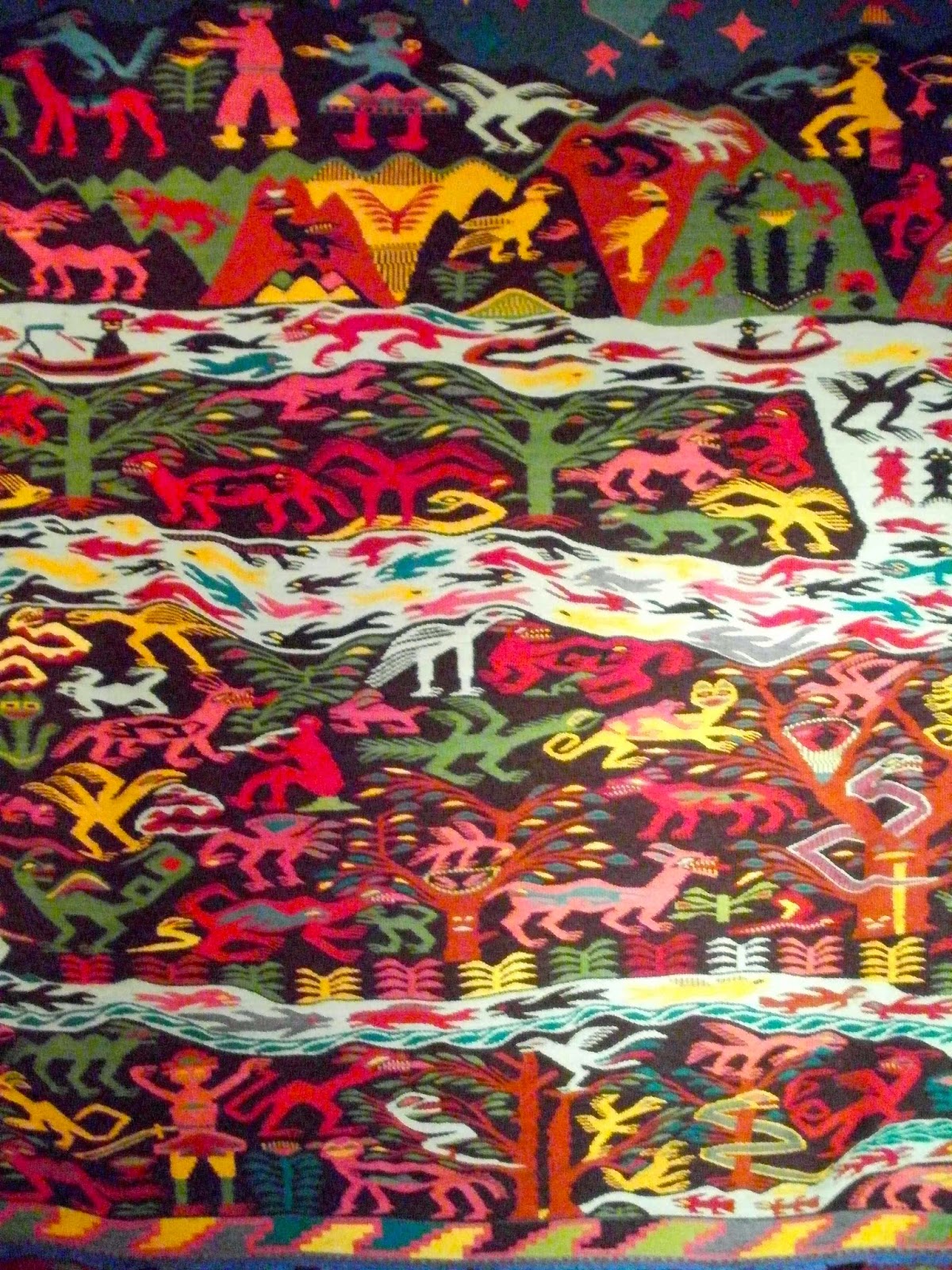

People of Bolivia

Before leaving Bolivia I’d like to share my limited observations of my sense of the people I encountered. There are two distinct cultures. The first lives in the Altiplano (high plain). It's situated between the western and eastern range of the Andes. The elevation starts at 10,000 feet above sea level and goes up. This area is predominately indigenous, the Aymara and Quechua (known as Incas) tribes are the majority . The people in the capital, La Paz, are representative of these societies.

La Paz at 14,000 feet above sea level is

the "highest" capital in the world

Lake Titicaca in the Altiplano is the highest lake in the world at 11,000 feet

Reed boat cruising Lake Titicaca

These ethnic groups practice traditional customs, speak indigenous languages, and dress distinctly different from Europeans and North Americans. Women wear round, full petticoat dresses, Bower hats, and speak some Spanish, if at all. Men wear fedora hats, dark wool suits from the 1950’s, and speak conversational Spanish, but no English. These cultures are a closed society and not interested in interactions with foreigners. Can you blame them? Last time they accepted outsiders -- Spanish adventurers and conquistadors -- these civilizations were robbed of their lands, mineral wealth (gold and silver), their heritage, their religion and forced to change cultural practices. As much as I tried, I was unable to penetrate the stoic, reserved attitude, and fear of outsiders. In my attempts to converse, I was either ignored or answered in one word (No or Sí) or brief sentences. No one asked any questions or attempted to get to know me.

Indigenous woman dressed in typical clothing of the Altiplano

Since most men have moved to the city for wage employment

in order to support families, the women do all the manual labor

in order to support families, the women do all the manual labor

The people of the Altiplano are very stoic and rarely smile

The second distinct culture is found in the lowlands of Amazonia, over the eastern slope of the Andes. People dress in modern clothing -- jeans (super tight for women), t-shirts, high heels, or athletic footwear. They are literate in western technology, cell phones and Ipods are everywhere. They listen to music from the USA, love watching Hollywood action movies, and follow the latest clothing fashions. They speak fluent Spanish, no indigenous languages, and are learning and speak some English. Generally, they were friendly towards me, talkative and curious about where I live, my travels, how I live in the USA, my work, whether I’m married, how many children I have (what do you mean you have no children? Why?), what type of car I own, and if they go to the USA, will they find work, and how much can they earn.

Juanita owner of Juanita's Hostal (recommended) in Villegrande

shared stories, laughter, and fellowship

Youth in Santa Cruz (a lowland city) live in the modern world

Modern lowland city of Santa Cruz de la Sierra

People from Santa Cruz are affluent, dress in modern fashion,

and are enjoying a Jazz concert

People from Santa Cruz are affluent, dress in modern fashion,

and are enjoying a Jazz concert

The Good

Angel is a young man in his early 20’s. He is elegant, patient, kind, and deliberate in his interactions with foreign travelers (when I grow up I want to be like him). He works as the receptionist at Hostal Residencia Bolivar (highly recommend) in Santa Cruz de la Sierra. In addition to Spanish, he speaks conversational German and French. He is studying English, which he finds difficult to master. Angel aspires to work for himself as an independent tour guide, sharing the wonders of Bolivia with visitors.

Angel an extraordinary young man demonstrating

his love of Bolivia's rich wild life

I had the good fortune to spend time with him. He tutored and helped me with my Spanish, editing and correcting a short story I wrote in Spanish regarding the conquest of Peru. As we worked together, he encouraged my style of writing. He said it’s “very graphic, dramatic, puts one in the scene, and we're not use to reading this perspective in our language”. He corrected grammar, word usage, while complimenting and motivating me to keep writing in Spanish. Angel supported me by saying, “your writing voice is very different because of your background as an English writer and North American.” He mentioned that, “some sentences have minor grammatical flaws that wouldn’t be written by a native Spanish writer. But, changing it would distract from your style, your emphasis, and weaken the story that puts the reader in the moment of action. I understood what you wrote and learned details of the conquest of Peru which I didn't know."

I reciprocated and helped him expand his English verbal descriptions and common phrases. When conducting tours, instead of telling an English speaker, “look at that bird”, he wanted to elaborate and give more details such as, “look at that beautiful red bird, with a long yellow beak, short blue legs, and a squawking chirp”. Upon returning to your home country, which description are you going to remember? Angel was conscious, sensitive and concerned that visitors have a positive, enriching experience. He is a young man with tremendous potential. I’m sure that one day he will realize his dream and manage his own tour agency that will be highly regarded.

The Bad

I’m on a semi-deserted street in Santa Cruz, Bolivia. It's the middle of the day and I'm waiting for a local transit bus to take me to the bus terminal to purchase a ticket to Argentina. A taxi pulls up in front of me. The back door opens. A squat, round, short, fat Bolivian, in his 40’s -- looked like a baboon with a beer gut -- wearing a cap with bright yellow letters spelling “Policía” (Police) sits in the back seat. He’s dressed in jeans, blue and red long sleeve plaid shirt, and not in a police uniform. In an aggressive tone he demands, “Did you just come from such and such hotel? Come here I want to talk to you.” He did not get out of the taxi. I tell him I don’t know the hotel. He responds in an angry tone of authority, “I didn’t ask you that. I asked if you came from that direction. Let me see your passport!” He said he was a policeman and quickly flashed an identification. Intuitively, I knew he was not a policeman. He was going to grab my passport, or worst rob me, and make his getaway. USA passports are a highly marketable commodity in the black market. I told him, “No sir, you’re not a policeman! I can’t help you. There comes my bus. I’ve got to go”. (essentially, Manny don’t play that game.) He got mad, shouted some insults and cuss words, slammed the door and speed away.

Authentic street police will always be in uniform

I shared this incident with Angel. He confirmed that police do not drive around in the back of cabs with just a cap saying Policía. Angel said the man was a thief with plans to get a hold of my passport and speed away. He apologized that a Bolivian would pull this scam on me, that it happens often enough, and that I did the right thing to walk away. Lesson learned: legitimate policeman wear uniforms, never approach a tourist asking to see their documents for no reason, are respectful and respond to inquiries in a courteous manner. If you’re ever approached in the above fashion, never, never hand over your documents or possessions. Immediately go to the police in uniform. In tourist areas they are always close by protecting visitors. Do not be intimidated by caps that say Police, identification, or tone of voice.

The Ugly

Throughout Bolivia, and most countries in Latin America, especially in the Altiplano, I’m challenged by people living in poverty and begging for money. Recently, I gave some money to an indigenous woman who had six young kids ages one to six years old sitting around her on the street. They all looked hungry. When I walked away, she sent four of the children after me. They surrounded me, blocked my path, and pleaded for money: “Something for me”, “I’m hungry”, “Help me, give me some money”. Though I felt guilty, I told them I already gave to their mother. They continued with their appeals, “But not to me!”, “Give me something!” I had to push my way through them with my hand in pocket holding on to my money and camera saying, “No thank you. No thank you.” They continued to follow me for a block, begging the whole way. Bolivians on the street were indifferent and ignored the scene.

The two Bolivian cultures clash: Indigenous woman

pleading with modern youth for money, they ignored her

At the bus station begging for money

The poverty is hard to witness, upsetting, and leaves one feeling helpless

I hurried down the street feeling frustrated, sad, angry, disappointed, and helpless. What more can I do? What more can my great country of abundance do? There is a limit to what I can afford to give. I finally had to say, “No!”, in a firm, almost angry tone. My final reaction tarnished any feelings of charity. Am I part of the problem by doing nothing more? Do I step up and become part of the solution? How?

One of the many ironies I face is that I have the funds to travel the world, eat well, and enjoy luxuries like clean water, three healthy meals a day, sometimes with dessert, and a secure home to live in. Yet the poor people I encounter in my travels only plead for money to eat one meal a day in order to survive. I’m very disturbed. I have no answers, only questions.